When families found themselves cooped up in the early days of COVID-19, many men got a new look at what it takes to keep a household humming. And lots of them pitched in on housework or child care tasks as they worked remotely.

Will those changes become a trend? That is hard to predict since men and women typically don’t even agree on who’s doing what or how well home chores are being done, a finding confirmed yet again by the latest American Family Survey.

The survey, now in its seventh year, examines relationships, attitudes, finances and other aspects of family life against the backdrop of current events, so the pandemic and its impacts dominate the 2021 version. The nationally representative poll released Tuesday is conducted by YouGov for the Deseret News and Brigham Young University’s Center for the Study of Elections and Democracy. It surveyed 3,000 adults between June 25 and July 8. The margin of error is plus or minus 2 percentage points.

Both unpaid work at home and employment changes during the pandemic show men and women may view labor differently, the survey found.

“Early on in the pandemic, there was much more work to do at home,” said Richard J. Petts, professor of sociology at Ball State University, who wasn’t involved in the survey. “Kids are home, no child care, all that additional stuff to do. Moms are doing more, but dads are also doing more. Dads stepped up and helped increase the number of families sharing work more equally.”

At the same time, work itself changed for many. Working remotely from home happened mostly for the wealthy: Seven in 10 high earners said they were sent home to work, compared to fewer than 6 in 10 in the middle and half of low-income workers, who disproportionately have front-line jobs.

Before March 2020, for all income categories, the share who worked from home at any time was between 41-46%.

After March 2020, high-income workers also worked from home more hours, doing so 54% of the time on average, compared to roughly 40% of the time for those earning less.

There were other work disruptions, too. Of the men working full time before 2020, 17% were temporarily laid off in the pandemic, 8% lost their jobs, 23% suffered income loss and 15% had hours reduced, the survey said. Women who’d been working full time were slightly less impacted jobwise: 15% were temporarily laid off, 7% lost jobs, 20% lost income and 13% had hours reduced.

Numbers were somewhat higher among part-time workers. Slightly more men than women were laid off, 35% to 32%. For both genders, 11% lost jobs. Among men, 35% reported losing income and a like 35% had hours reduced, compared to 34% of women working part time who lost income and 23% who had hours reduced.

Mopping and paying bills

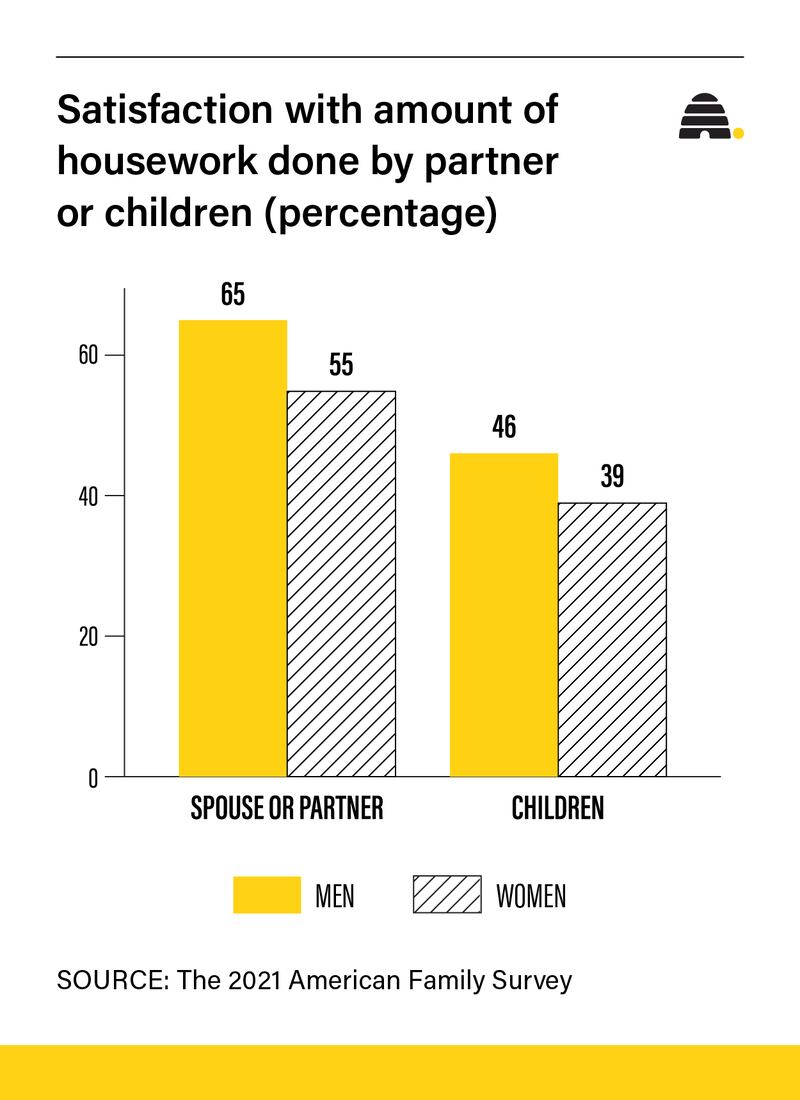

Asked who does what, men in the survey were more apt to say they pay the bills but they share housework with partners about evenly. Women often agreed men are more likely to pay bills, but they scoff at the 50-50 chore split, claiming they themselves do two-thirds of the work. They do it better, too, they say.

“One thing we learned is women rate men as being more generally unfair and not contributing as much,” said Jeremy C. Pope, who both co-wrote the survey report and co-directs the center at BYU with Christopher F. Karpowitz. “They are also a little disappointed in their kids. But it’s probably also true that women have higher standards for how much others should be contributing and think everybody should be pulling their weight more. That doesn’t mean women have unreasonable standards, but I do think they have higher standards.”

Pope said divergent views can lead to levels of dissatisfaction.

And both could be wrong, Karpowitz added.

Petts said men’s involvement at home impacts a range of outcomes for families, not least whether moms have high-quality time with kids. And a father’s involvement pre-pandemic was a “huge predictor” of whether mothers voluntarily left the labor force when the pandemic hit. He said some experts believe dad’s involvement level at home will likely help determine whether women go back to work, too.

Petts noted — and the survey confirms — fathers perceive their partners are critical of the way they do chores. Dads may also misunderstand whether women enjoy some of the tasks and veer away from doing them for that reason.

Not all women complain their husbands slack off at home.

There’s a lot to do in the Springville home where Emily and Isaac Arnott are raising six boisterous kids. Mary, 9, William, 8, David, 6, Jane, 4, Henry, 2, and newborn Hyrum could create chaos if their folks don’t help each other out.

The Arnotts recently moved to Utah from Mentone, California, where he worked on a farm his family owns. She worked part time. In the pandemic, he worked remotely about half the time. Since the move, he’s become a full-time graduate student working on an advanced business degree.

They did a lot of work around the house during COVID-19, including renovations. He still helps with housework — cleaning bathrooms, doing yard work, washing the dishes at night.

But it wasn’t always that way. They were married when he was 22 and she was 20 and “it’s been a process to learn to become adult, to grow together and be more aware of each other’s needs,” she said.

“When he does housework, he’s owning his home, is being a good steward over his home, which has been a huge shift. The truth is, this is not my home. These are not my dishes. This is our home, these are our dishes or our bathrooms. So when he helps in the home, he’s doing it for us,” said Emily Arnott, now 30.

Petts, too, has taken on more of the tasks at home with his children, 7 and 8, since his wife started a new job with an inflexible schedule. He’s not sure he does half the housework, but he does more than he did.

“I now definitely have a greater respect for both sides of the coin,” he said.

Work and a career path

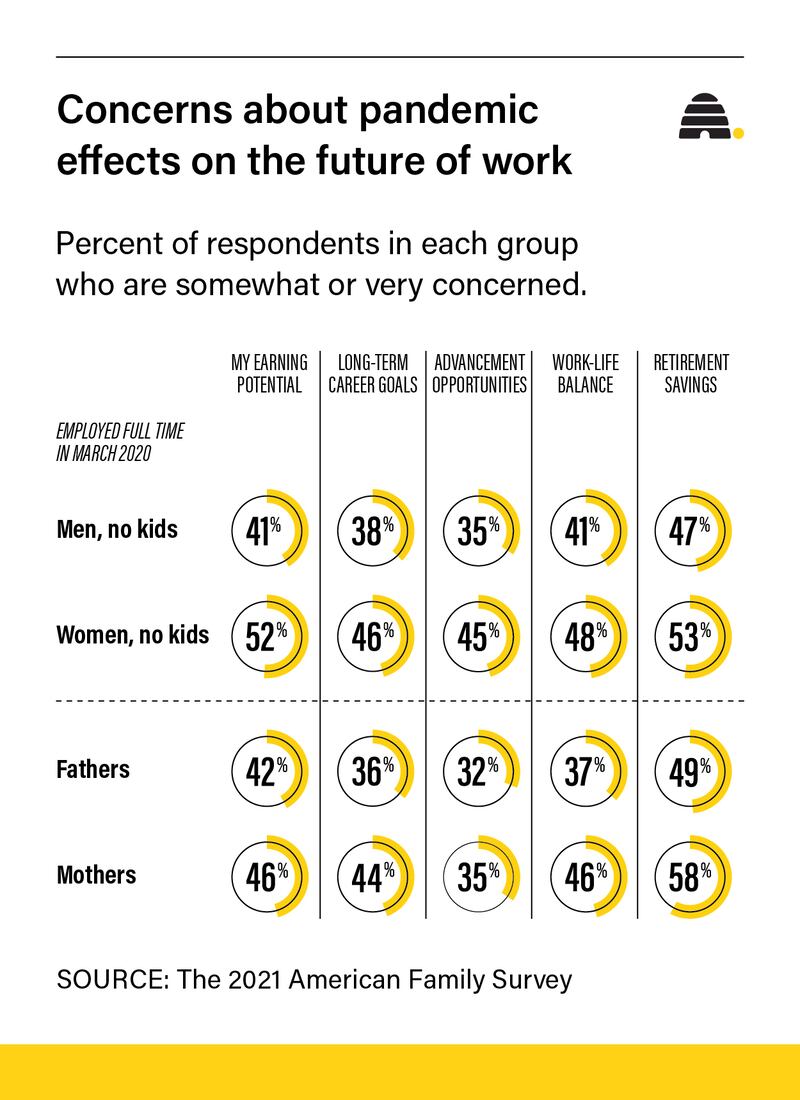

The survey asked those who worked full time prior to the pandemic if they had concerns related to the future of their careers. Women were consistently more worried than men about things like earning potential, the impact on promotions or long-term goals, work-life balance and retirement savings.

While the sexes both agreed that working full time can complicate work-life balance, the biggest weight was felt by working mothers.

That’s not new. In 2019, before the pandemic, Pew Research Center found 72% of working mothers with minor children were employed at least part time and 55% had full-time jobs, compared to just over half who worked in 1968. Nearly 9 in 10 fathers with minor children worked full time throughout both periods.

Similar to the American Family Survey, that survey found working parents, but especially working mothers said that role made it hard for them to progress in their career. And even before the pandemic, Pew found more than half of working moms and 4 in 10 working dads said they needed to reduce work hours as they juggled employment and parenting.

Would they quit? Not then and not now. Both the American Family Survey and the earlier Pew study found a large majority of parents say work is what’s best for them.

Pew’s big difference came when working parents were asked what was best for families with young children, not about their own situation. Just over three-fourths said working full time is ideal for fathers; one-third said that for mothers. And more than 1 in 5 said not working for pay at all is best for mothers of young children.

Not all American Family Survey work-related questions were about the pandemic. Working mothers and fathers were asked about work-life balance and if it’s easier or harder because they combine parenting and work. Mothers in greater numbers thought being a working parent made things harder — especially those working full time compared to mothers working part time. The latter worried less about both parenting and career advancement.

Yet the vast majority of parents who work full time say they want to work full time. “It’s not like there’s some huge desire among full-time working moms or dads to be doing something different, but they’re feeling the work-life balance challenges in different ways — and women seem to feel that challenge both at home and at work,” said Karpowitz.

“For them, being a working parent complicates their parenting life. And it also is more likely to complicate their career life than what we see among men,” he said. “Those are interesting differences in perception, and I am sure they have a lot to do with social norms and expectations that differ across the genders.”

While some surveys suggest women prefer part-time work or more work flexibility, Pope points out such preferences are largely driven by family situations that a survey doesn’t always capture well. Caregivers have different work challenges than those who aren’t. Where you live impacts job opportunities and challenges, too.

The pandemic has also provided workers with more opportunities to choose who they like to interact with, said Emma Zang, an assistant professor of sociology at Yale University who was not involved in the American Family Survey. And technology offers new tools to improve social interaction. Remote work gave those a boost.

But she expects remote work will receive some opposition post-pandemic from bosses who fear they’ll lose control of employees. And it’s harder to create company culture with remote workers.

The pandemic has likely opened and closed work doors that may impact men and women in unexpected ways, she said.

Who’s watching the kids?

Child care is crucial for some workers, as the pandemic made clear.

Among those working full time, fathers (69%) far more than mothers (48%) believe they and their spouse take care of child care needs. But 38% of women say they rely on extended family, compared to one-fourth of men. Among part-timers, 90% of fathers say they and their spouse provide the child care, compared to 79% of mothers. Fewer than a quarter of parents working full time say they rely on day care. And 11% of each gender say older siblings provide a younger child’s care.

“Whether they work full time or part time, fewer working women than men are able to meet their child care needs themselves or with the help of their partners,” the report said.

“My guess is men are relying on their spouses, which women aren’t able to do as much if they’re in the workforce. In any case, they’re feeling the burden of how to provide child care in different ways,” said Karpowitz.

Children are more likely to complicate a woman’s work life and career trajectory than a man’s, he noted.

Still, more than 80% of working mothers and fathers believed their workloads are right for them at this stage in their lives. So do those not working or working part time, though at least 1 in 4 mothers who are not working for pay said they would like to, at least part time. Demographers often refer to “working for pay” instead of “working outside the home” because many women in particular work remotely from home and just saying “working” sounds like taking care of the home is not work.

Mario Carrillo, 36, has worked from his home office since 2017. But for his wife, Angelica Rodriguez, 30, who recently gave birth to their daughter Izel, working remotely was new when COVID-19 closed offices. The nonprofit she works for in Austin, Texas, sent workers home and Carrillo was kind enough to let her take over his office. He moved to the kitchen table, she said.

He’s helpful like that and sometimes does more housework than she does — especially vacuuming. But how they’d manage to parent and work, which is no longer all remote, would have been challenging if her mother wasn’t helping. “She’s dropped everything and provides day care for our girl,” Rodriguez said.

They hope Izel will grow up knowing she has choices: Stay home and raise a family. Work. Or, do both, as her parents do.

Not everyone can call on family for child care, though. Infrastructure is crucial in a society where women in the labor force still do most of the domestic labor, said Barbara J. Risman, editor of the journal Gender & Society, and distinguished sociology professor at the University of Illinois Chicago. America’s infrastructure for working parents isn’t that great, said Risman, who wasn’t involved in the survey.

Child care infrastructure refers to elements, often supported by government funding, that make care high quality, accessible and affordable, from subsidies for low-income parents to training and even wages for child care providers.

“Often women were in totally impossible situations because they were both trying to make a living and do the work that they used to pay somebody else to take care of their children,” said Risman, a Council on Contemporary Families senior scholar. “So of course we had a major crisis which then has possibly long-term implications if we don’t come up with social policies” to help families balance responsibilities.

That infrastructure, she added, is crucial to economic success for both nations and families. President Joe Biden’s administration has taken that position, too, in pushing for his family policy bill that is stuck in Congress.

Risman said it’s not solely a problem for mothers. In a small but growing share of families, fathers take on primary duties as caregivers. Single parents are always the hardest hit.

We are in “a historical moment where we could really as a society show we have learned something from the pandemic,” Risman said. “We have never redesigned the labor force with the express intention of making sure that it is an equitable place for people who are also caretakers.”

Most people, she added, will at some point bear that title.

alt=Lois M. Collins

alt=Lois M. Collins