A version of this story appeared in CNN’s Race Deconstructed newsletter. To get it in your inbox every week, sign up for free here.

I inwardly breathe a weary, cyclone-force sigh whenever I hear the words “critical race theory.”

My issue isn’t with CRT, which is a movement that emerged in the 1970s to challenge the spurious notion that the law is impartial. I’m exhausted by Republican lawmakers’ antics in recent months that have warped CRT into a repository of vague topics they don’t like.

Take what’s happening in Texas. This week, a social studies law inspired by the political right’s backlash to CRT went into effect, circumscribing how educators in the state can talk about race and racism.

“This is very clearly an attack on diversity, equity (and) inclusion. It very much feels like a political overreach based on misinformation,” Ana Ramón, deputy director of advocacy at the Intercultural Development Research Association, told CNN’s Nicole Chavez. “Teaching critical race theory in K-12 would be like teaching quantum physics in K-12. … There’s no curriculum that has been adopted in Texas classrooms.”

Maybe the most disturbing thing about the tub-thumping about CRT (which, it’s worth repeating, isn’t taught in grade school) is that the core impulse is hardly new – but instead fits into a long, messy history of fights over classroom instruction. As students return to school, adults could benefit from more context about what’s going on.

Here’s what these ever-simmering battles reveal about the US’s socio-political anxieties over, among other things, race, gender and immigration.

How did the backlash to CRT creep into schools?

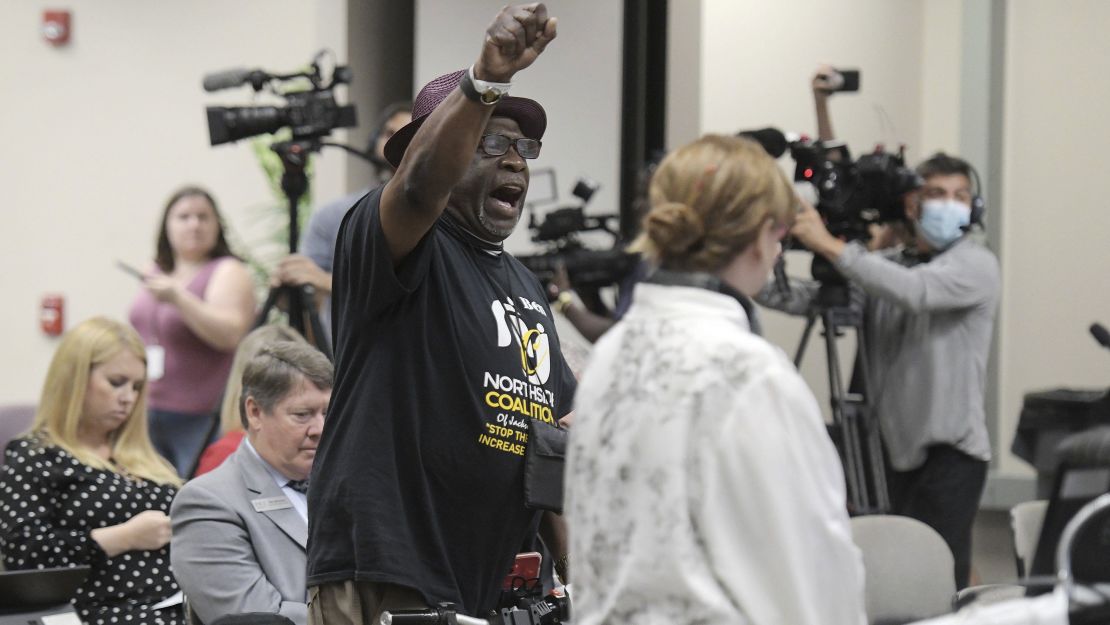

Across the country, conservative advocacy groups and Republican-dominated state legislatures – abetted by Fox News, as CNN’s Oliver Darcy has pointed out – are exploiting relatively minor local school disputes, mutating anodyne school board meetings into eye-popping spectacles where people contest historical facts.

Republicans trust that playing up these conflicts will be electorally useful to them, as they train their attention on the 2022 midterms and beyond.

The orchestrated attack on CRT takes a toll on teachers, staff and students.

“The more we remove the ability to have these critical and crucial conversations, we are going to continue to whitewash the system that is already whitewashed,” Shareefah Mason, a master social studies teacher at Dallas’ Zumwalt Middle School, told the Texas Tribune.

Or here’s how Christopher Caltagirone, a school board member in Phoenixville, located in the suburbs of Philadelphia, described the situation to my CNN colleagues: “I think it’s a knee-jerk reaction to what’s gone on in society over the last year. It’s a conflation of issues. It’s all being put together. And I don’t think that’s fair.”

It isn’t a stretch to say that the current struggle over how schools teach not just history but the ways history moves in the present might affect students’ understanding of the world around them for years to come.

Is this the first time the political right has freaked out over learning about race and racism?

No. This dispute has existed in a variety of forms since at least the 1800s.

For instance, as the writer Anthony Conwright recently traced for Mother Jones, in 1829, North Carolina sought to quash stirrings of slave uprisings by prohibiting the distribution of abolitionist literature. One law made it a felony to circulate “any written or printed pamphlet or paper … the evident tendency whereof would be to excite insurrection, conspiracy or resistance.” Another law proscribed “the teaching of slaves to read and write” because doing so “has a tendency to excite dissatisfaction in their minds and to produce insurrection and rebellion to the manifest injury of the citizens of this State.”

North Carolina’s insistence on limiting Black instruction was no historical aberration: “The tactics of suppression have everything to do with a deep national anxiety about Black people’s dissent, whether we’re talking about slave insurrections or the (Black) Panthers or Black Lives Matter,” the University of Illinois at Chicago professor Jane Rhodes told me in February.

In the second half of the 19th century, a different fight erupted: how to talk about the Civil War in schools. To no one’s surprise, the South wanted to reframe the war in a manner that was sympathetic to the antidemocratic Confederacy, laying the foundation for the enduring Lost Cause myth. The United Daughters of the Confederacy played a big role in this reeducation campaign and sought to jettison “long-legged Yankee lies” from textbooks.

Agitation over how schools ought to discuss the legacy of slavery persists into the present. Recall how The 1619 Project sent Republicans into a full-blown racial panic, with many looking to use the power of the state to suppress the project’s use in classrooms.

Have there been education disputes over things other than race?

Afraid so.

For instance, World War I set off a burst of xenophobia aimed not only at German immigrants and Americans of German descent but also at the German language. Senator William H. King of Utah introduced a bill to ban teaching German in Washington’s public schools.

“Wherever goes the German language goes, too, the insidious, malicious, stealthy, cruel, coldblooded propaganda to stifle the liberties of free peoples,” King said in 1918. “We owe a duty to our children. We must protect them from the German monster by removing the trap – the German language.”

In September of last year, Seth Cotlar, a professor of history at Willamette University, noted on Twitter how, in 1923, amid widespread fear of communism and immigration, Oregon’s state lawmakers tried to smother supposed leftist threats.

More specifically, the legislature, made up of a near-majority of Ku Klux Klan members, passed a law that banned the use in public schools of any textbook that “speaks slightingly of the founders of the republic, or of the men who preserved the union, or which belittles or undervalues their work.”

And in her 2015 book “Classroom Wars: Language, Sex and the Making of Modern Political Culture,” Natalia Mehlman Petrzela, a professor of history at The New School, interrogates how, in the 1960s and ’70s, spurred by the era’s countercultural ethos, grassroots citizens in California “came to define the schoolhouse and the family as politicized sites” through scrimmages over Spanish-language and sex education.

“Fights in and about the classroom – classroom wars – formed a crucial crucible in which the powerful political notion of ‘family values’ was contested and constructed,” she writes.

So while the present-day backlash to CRT might feel unique, really, it’s not. It’s just the latest iteration of an age-old tendency to turn the classroom into a battlefield.